The Home

The Cukrov family called 20 Dalison home for more than sixty years, holding out for the last twenty against a controversial industrial redevelopment that slowly erased more than 300 surrounding homes. Now, it too awaits demolition.

The home at 20 Dalison in 2015, when it was still occupied and well-manicured by members of the Cukrov family.

The home at 20 Dalison was built in the late-1950s by Marijan and Yolanda Cukrov, who migrated to Western Australia from former Yugoslavia in 1951. Marijan had already been living in Western Australia in the late 1940s, and the pair met on his return home before migrating back to Western Australia permanently.

Marijan and Yolanda were part of a cohort of postwar migrants from Eastern Europe and elsewhere who were settling around the state as Australia’s immigration policy started to widen. They took up jobs in Fremantle; Jolanda at the old South Fremantle Mills & Ware — which eventually merged into the iconic Arnott’s Biscuits — and Marijan at Fremantle Bunnings, a home renovation supplies warehouse that's synonymous with Australia's promise of the suburban good life.

10 March 1951. Marijan (right) and Yolanda (left) Cukrov on their wedding day in Croatia (then Yugoslavia).

Perth’s southern suburbs were commonly chosen for farming, and like other families, the Cukrovs recognised the soil quality in Wattleup (est. 1931) and relocated there to cultivate a market garden. This eventually came to constitute their full-time livelihood, as was the case for many in the Wattleup area — and still is for those remaining today.

c.1970. Marijan Cukrov in the family's market garden at 20 Dalison.

Western Australian suburbia was booming at the time, and the Wattleup community quickly grew into a thriving rural-residential suburb with a densely populated township, of which 20 Dalison formed part. Nestled between the Indian Ocean and the bush, Wattleup perfectly embodied the budding cultural notion of the "Australian dream”, and it became a long-term home for many residents.

At first, Marijan and Yolanda lived at 20 Dalison with their two sons, Jim and Gary, as well as an uncle — who all shared just two small rooms. Eventually, they built on to the front of the house in the mid-century Eastern European style typical of that era. A permanent feature of 20 Dalison was the lovingly manicured front garden and lawn, maintained by Yolanda for the seven decades she lived there.

c. 1965. The Cukrov family. (L–R: Gary, Marijan, Yolanda and Jim Cukrov.)

In 1996, Wattleup and nearby Hope Valley were earmarked for redevelopment by the Western Australian state government, which they started buying homes from residents to facilitate. That was more than twenty years ago. The redevelopment, now named “Latitude 32”, is yet to commence, and a scattering of hold-out homes remain. In the township, just 20 Dalison and one other home still stand.

Successive governments have faced much scrutiny for ongoing mismanagement of the area and it has been derided as a major planning blight, labelled the “suburb the WA government forgot”1.

Throughout this time, there was an added layer of tension between some Wattleup residents and the state government with the emergence of a perceived cancer-cluster. The suburb is located inside the area’s industrial buffer zone, which exists to manage the impact of emissions from nearby production such as the Alcoa Alumina Refinery and Cockburn Cement.

A 2017 health report revealed that Wattleup and the surrounding Kwinana area had experienced one of the highest rates of colorectal cancer deaths, positive results from bowel cancer screening, and lung cancer death in Perth in recent years. It is now acknowledged by the Department of Health and the Environmental Protection Authority that living in Wattleup and Hope Valley exposed residents to potentially toxic air quality that significantly heightened their chances of ill health.

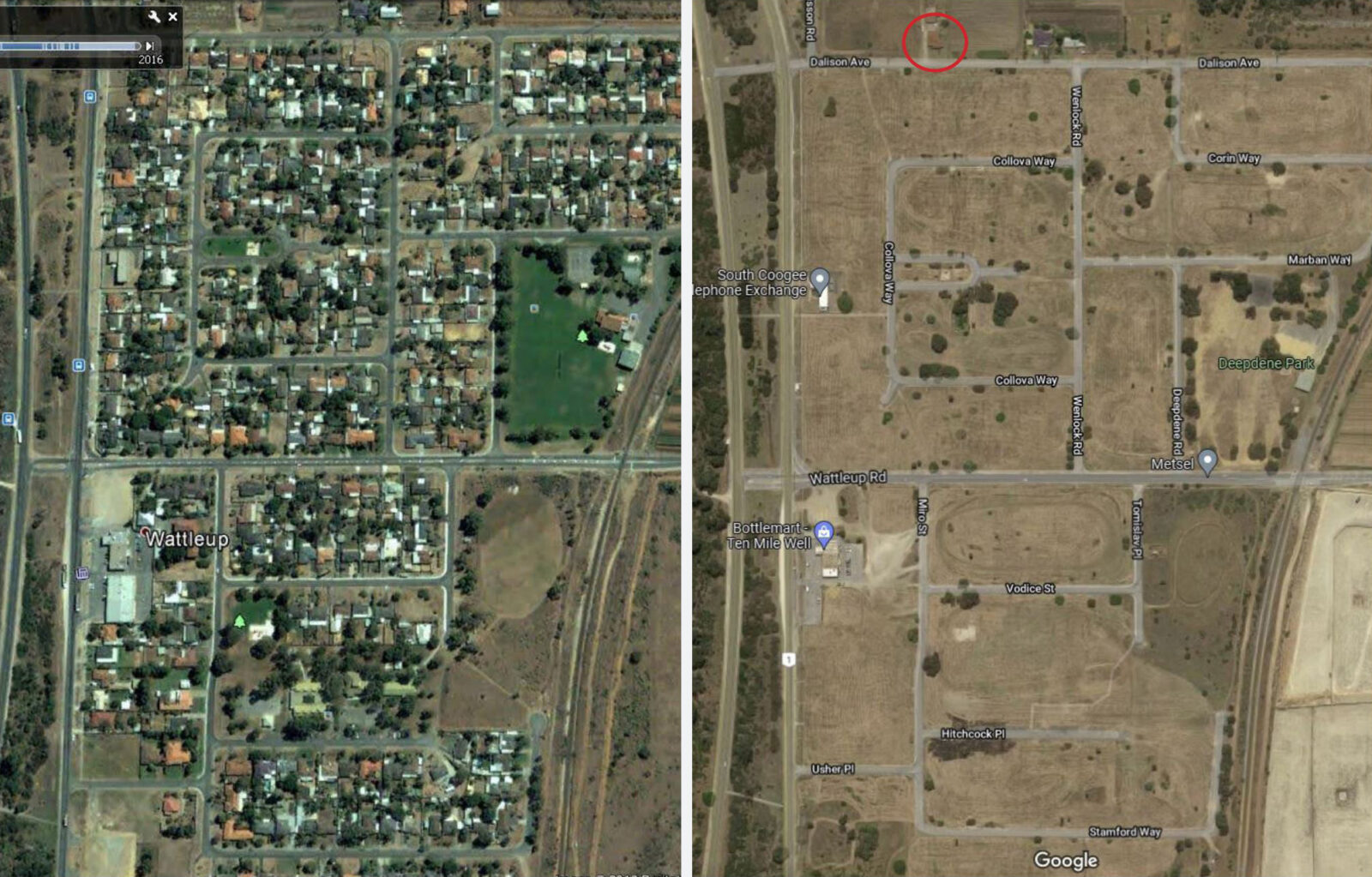

December 2021. In 1996, the Western Australian state government earmarked Wattleup and nearby Hope Valley for one of the state's largest-ever industrial redevelopments. Since then, more than 300 homes have been demolished here, leaving what was once the densely populated Wattleup township eerily abandoned.

However, Jim and Gary Cukrov say that many residents also lived very long lives in Wattleup, which they attribute to their years of hard but healthy and happy work in their gardens. News reports and research conducted in the development of the Dalison work revealed accounts of residents who didn’t want to leave.

Jim and Gary also recalled many residents questioning why they should have to: a high proportion of residents were in their twilight years and wanted to enjoy their retirement in their own homes. They say the offered rate for their properties didn’t seem fair, with the government poised to reap enormous profit from the industry that would replace their houses.

Left. 20 Dalison and the surrounding suburb in 1989 Right. 20 Dalison and the surrounding suburb in late 2020

This slow and conflicted process has left Wattleup eerily abandoned, suspended in time. In the old Wattleup township, the old blocks are still recognisable; footpaths and driveways remain, palm trees still stand, even old fennel plants linger. But the homes are missing.

Former residents have been left heartbroken and confused as to why they were forced to relocate when development still hasn’t occurred; particularly in light of the brand new residential developments only a few kilometres to the east. Vivente Living and Quenda Living estates, as well as Aigle Royal Group’s “Wattle Rise”, are all situated in the new suburb Hammond Park, which was created in 2002 within six kilometres of Wattleup. Along the roads leading into the now-desolate old suburb, bright banners flap in the wind advertising “dream homes” and a lifestyle defined by safety and ease.

December 2021. Brothers Jim (right) and Gary (left) Cukrov, who grew up at 20 Dalison with their mother, Yolanda, and father, Marijan Cukrov. After their aging mother refused to give up her home for more than two decades, she died peacefully at home in July 2019. Jim and Gary decided to sell the house to the state government in the wake of her passing.

For Jim and Gary, 20 Dalison was one of their first homes. Their mother and father lived in it for most of their lives, and so did they. After Marijan died, Jim lived there with his mother Yolanda as she aged. She wanted to hold out. Jim says she "wanted to die in Wattleup".

Yolanda died peacefully at home on July 31st, 2019. Jim and Gary finally made the emotional decision to sell the home to DevelopmentWA in the wake of her passing. It now awaits demolition, leaving the family’s long-time neighbour and friend Peter Rokich as the last remaining resident of the Wattleup township.

2016. Jim and his mother Marijan out the front of their home at 20 Dalison, with the old Wattleup township in the background.

DALISON attempts to pay tribute to the Cukrov family’s memory, while also acting as an index for the more than 300 homes that once populated this suburb. It also sits in dialogue with other works in Strange's decade-long practice, working with the home as both a real place with local specificity, and also a highly recognisable symbol loaded with notions of safety, security and even success.

The work attempts to evoke some of the strong emotions that reside within 20 Dalison—joy, grief, nostalgia and a sense of solitude. In this way, the work reflects on the special connection hold-out homeowners have to their properties and the many layers of home and memory to which this phenomenon speaks.